EMDR: Treating Trauma in the 21st C.

By Susan Epstein, LCSW

This piece was originally published on https://thewoolfer.com/2018/08/17/emdr-treating-trauma-in-the-21st-century 8/18

Thirty years ago, a woman named Francine Shapiro began to explore various approaches to healing and self-care after she was diagnosed with cancer (no doubt a Woolfer at heart!). One day, while walking through the park (or so the origin story goes), something upsetting came to her mind, and her eyes started to move back and forth involuntarily. When she slowed the movement down, and continued it more deliberately, she felt calmer. That simple observation, along with her curiosity, creativity, and painstaking clinical efforts, led her (and many others) to develop “Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing,” or EMDR for short.

Shapiro was a true feminist hero. Defying mockery, disbelief, and the dismissals of mainstream colleagues and the therapeutic establishment, she trusted her intuition to transform her subjective experience into a method that would help other people in pain.

Thirty years later, people are using EMDR all over the world to help survivors of trauma heal themselves and move on with their lives. While EMDR still has its skeptics and detractors, it is increasingly endorsed by rigorous and “scientific” studies. (I put “scientific” in quotes, because whenever issues of mental health are concerned, the effort to draw universal conclusions about human wellness are, I believe, a bit reductive, but that is an issue for another discussion.) By 2014, the results of more than 24 randomized controlled studies showed that EMDR had more rapid and sustainable resolution of PTSD symptoms than were achieved with other therapeutic approaches. The Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense, and American Psychiatric Association, among other institutions, now recognize EMDR as the preferred method for treating prolonged reactions to trauma. Quite simply, EMDR works — not for everyone — but for a great majority of people who undergo the treatment.

How to Find an EMDR Therapist

As with most forms of effective therapy, the rapport between client and therapist, the so-called “therapeutic alliance,” is of key importance. Here, clients should trust their gut. Indeed, it can be hard to find an EMDR therapist at all, depending on location and cost. The training for therapists itself is expensive and the majority of EMDR practitioners do not accept the low reimbursements provided by insurance companies.

It’s always a good idea to ask about a therapist’s experience level. For more straightforward traumatic experiences, like a car accident or isolated sexual assault, a younger, less experienced clinician might be fine; for complex trauma experienced over the course of childhood, in an abusive marriage, or from serving in a war zone, EMDR alone may not be as effective and a more seasoned therapist who can draw on eclectic therapeutic approaches in addition to EMDR may be in order. EMDR may be used in conjunction with psychopharmacological treatments, group therapy, and variations on talk therapy like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT).

So What’s It Like to Undergo EMDR?

In Shapiro’s EMDR model, the therapist takes the client through eight phases. The initial steps deal with History Taking, Treatment Planning, and Assessment. Having heard of EMDR’s ability to cure people quickly, some clients are not expecting to put in the time it takes to do this preparatory work (usually one to two sessions, sometimes more). But it’s important to be equipped with tools to help you deal with the strong emotions that may emerge in the course of the treatment.

A therapist will first screen for undiagnosed Dissociative Identity Disorder (aka multiple personality disorder), a condition that is unfortunately not as rare as we might like to believe. Basically, this entails asking the client a series of questions to make sure he/she/they do not rely too much on dissociation — a mental state in which thoughts, memory and one’s sense of identity are altered and disconnected to varying degrees — as a prime defense against feeling painful emotions like hurt, sadness, and anger. If dissociative tendencies exceed a certain level, the treatment may unleash more repressed emotion than the client can manage and thereby be contraindicated.

A therapist should help the client establish a “safe enough place,” i.e. somewhere real or imagined, past or present where the client feels as safe and comfortable as possible. We work on helping the client develop the ability to transport themself there through visualization and relaxation. This is something that is practiced before reprocessing, so the feeling of being safe can be summoned up at any time if a client becomes overwhelmed by uncomfortable emotions or unexpected memories. The therapist is trained to help clients with this process, and her presence should have a calming effect.

Assessment Phase

The Assessment phase involves discussing with the client so-called “target memories.” We usually ask clients to create a list of up to 10 such incidents and rate each one on a scale of 0-10, where 0 is neutral and 10 is the most disturbed one can imagine being. The history-taking process may aid in this process by uncovering important material. As for where to start, the choice of memory is up to the client. Some like to begin with something mildly or moderately upsetting in order to get used to the process; others prefer to jump into the hardest memory first just to get it over with. There is no right way.

Next, the clinician asks the client to bring the target memory to mind and answer a series of questions about the emotional, cognitive, and physical experiences in the present brought up by the memory. This holistic approach is a key aspect of the EMDR protocol. Traumatic experience affects people physiologically (i.e. the flashbacks and panic attacks that can occur in PTSD, for example); they can also affect clients’ feelings and beliefs about themselves, whether conscious or unconscious. So we ask clients to identify feelings when thinking of the traumatic memory (the negative cognition, i.e. “I’m trapped” or “I’m unlovable”), and then how they would like to feel (the positive cognition, i.e. “I’m strong enough,” or “I have good qualities”). We also ask clients to rate how “valid” that positive cognition feels (VOC) on a scale of 0-7. The success of the procedure is partly measured by clients’ increasing identification with the positive cognition.

Unlike many forms of talk therapy, where clients are encouraged to speak freely and go into great detail about issues they find distressing, in EMDR, only the most basic descriptions are required (i.e. “I keep thinking about something that happened with my ex-husband” or “I witnessed a terrible fight between my parents when I was eight”). Clients can share as much, or as little, as they want. What is most important is to identify the right target memories for treatment. The therapist’s role is to prepare clients emotionally for what they may experience during the reprocessing, and to help them trust the process without needing to force anything to happen.

Desensitization Phase

Finally, we come to the reprocessing of the traumatic memory, the so-called Desensitization phase. When Shapiro first developed EMDR, she used her finger to guide clients’ eyes back and forth to create what we refer to as bilateral stimulation (BLS) of the brain. Other forms of BLS include tapping the client on the right then left leg or arm or hand, using audio stimulation in the right then left ear, or having the client hold discs that vibrate first in the right and then in the left hand. Some clients prefer to keep their eyes closed, making these alternatives especially useful. Nowadays, many clinicians use light bars with LED lights that move or jump back and forth to give the client something to focus on (and save the therapist shoulder pain!). The speed can be adjusted and the angle of the bar changed to provide the client with the most comfortable and effective experience possible. Again, there’s no right way to do it and, if reprocessing is stuck, a change in the direction or speed of the eye movements (or other BLS) can break through the impasse.

After the prompting of the series of questions in the Assessment phase, the client brings the disturbing memory to mind again and begins some form of BLS. The therapist instructs the client to see what comes up, as if watching a movie or scenery out the window of an advancing train. The therapist may talk intermittently throughout the reprocessing (“Just let it come,” “You’re doing great,” “Keep breathing easily,” “It’s just old stuff”); this creates a dual consciousness for the client, being caught up in past memories while still aware of being present in the here-and-now of the therapy office. The client can stop at any time, which adds to a sense of safety and control.

As the BLS proceeds, memories may emerge of related incidents from other times in the client’s life or the target memory may change and new details become noticeable to the client as the reprocessing continues. The therapist intermittently stops the BLS, instructs the client to take a deep breath and asks, “What are you getting now?,” directing the client to go with whatever emerges.

Sometimes clients report that the image has not changed after several sets of eye movements. This is known as “looping.” The therapist may then suggest the client consider something different about the image (“What if she could talk back?” or “Could anyone else join this scene?”). This is known as the “Cognitive Interweave” and may effectively get the reprocessing moving again. As the client experiences various images and memories, repressed emotions often emerge (aka abreaction). This can be very painful, but is very much the goal of treatment. Once the repressed emotion has been released, clients usually report great relief. Some clients do not even feel upset by the process, but report a sudden shift in perspective until the memory no longer seems upsetting.

Installation Phase

The Installation phase of the treatment involves revisiting the VOC and determining that the positive cognition feels completely true to the client. If it does, we move on to the Body Scan phase, in which the client is invited to scan for tension or discomfort in their body. More sets of BLS are undertaken until the tension is neutralized. The Closure phase may involve taking time to visualize the safe space or do other things to help the client contain any remaining upsetting material or sensations until the next session.

It is not uncommon for clients to feel emotionally raw after this work, and vivid dreams are not uncommon. We suggest clients keep a journal to allow for further processing (and reprocessing) of thoughts, feelings, and new memories released by the EMDR. If there is lingering disturbance associated with the original memory in subsequent sessions (the Reevaluation phase), further reprocessing may be undertaken.

After EMDR, clients often report that they no longer find the target memories disturbing. The client understands that the trauma is in the past, and they are no longer vulnerable to the same victimization or terror, either because their environment has changed or they now have resources with which to respond to dangers effectively. The memory has not disappeared, but the negative emotional effect it has on the client has been neutralized.

In Shapiro’s EMDR model, the therapist takes the client through eight phases. The initial steps deal with History Taking, Treatment Planning, and Assessment. Having heard of EMDR’s ability to cure people quickly, some clients are not expecting to put in the time it takes to do this preparatory work (usually one to two sessions, sometimes more). But it’s important to be equipped with tools to help you deal with the strong emotions that may emerge in the course of the treatment.

A therapist will first screen for undiagnosed Dissociative Identity Disorder (aka multiple personality disorder), a condition that is unfortunately not as rare as we might like to believe. Basically, this entails asking the client a series of questions to make sure he/she/they do not rely too much on dissociation — a mental state in which thoughts, memory and one’s sense of identity are altered and disconnected to varying degrees — as a prime defense against feeling painful emotions like hurt, sadness, and anger. If dissociative tendencies exceed a certain level, the treatment may unleash more repressed emotion than the client can manage and thereby be contraindicated.

A therapist should help the client establish a “safe enough place,” i.e. somewhere real or imagined, past or present where the client feels as safe and comfortable as possible. We work on helping the client develop the ability to transport themself there through visualization and relaxation. This is something that is practiced before reprocessing, so the feeling of being safe can be summoned up at any time if a client becomes overwhelmed by uncomfortable emotions or unexpected memories. The therapist is trained to help clients with this process, and her presence should have a calming effect.

Assessment Phase

The Assessment phase involves discussing with the client so-called “target memories.” We usually ask clients to create a list of up to 10 such incidents and rate each one on a scale of 0-10, where 0 is neutral and 10 is the most disturbed one can imagine being. The history-taking process may aid in this process by uncovering important material. As for where to start, the choice of memory is up to the client. Some like to begin with something mildly or moderately upsetting in order to get used to the process; others prefer to jump into the hardest memory first just to get it over with. There is no right way.

Next, the clinician asks the client to bring the target memory to mind and answer a series of questions about the emotional, cognitive, and physical experiences in the present brought up by the memory. This holistic approach is a key aspect of the EMDR protocol. Traumatic experience affects people physiologically (i.e. the flashbacks and panic attacks that can occur in PTSD, for example); they can also affect clients’ feelings and beliefs about themselves, whether conscious or unconscious. So we ask clients to identify feelings when thinking of the traumatic memory (the negative cognition, i.e. “I’m trapped” or “I’m unlovable”), and then how they would like to feel (the positive cognition, i.e. “I’m strong enough,” or “I have good qualities”). We also ask clients to rate how “valid” that positive cognition feels (VOC) on a scale of 0-7. The success of the procedure is partly measured by clients’ increasing identification with the positive cognition.

Unlike many forms of talk therapy, where clients are encouraged to speak freely and go into great detail about issues they find distressing, in EMDR, only the most basic descriptions are required (i.e. “I keep thinking about something that happened with my ex-husband” or “I witnessed a terrible fight between my parents when I was eight”). Clients can share as much, or as little, as they want. What is most important is to identify the right target memories for treatment. The therapist’s role is to prepare clients emotionally for what they may experience during the reprocessing, and to help them trust the process without needing to force anything to happen.

Desensitization Phase

Finally, we come to the reprocessing of the traumatic memory, the so-called Desensitization phase. When Shapiro first developed EMDR, she used her finger to guide clients’ eyes back and forth to create what we refer to as bilateral stimulation (BLS) of the brain. Other forms of BLS include tapping the client on the right then left leg or arm or hand, using audio stimulation in the right then left ear, or having the client hold discs that vibrate first in the right and then in the left hand. Some clients prefer to keep their eyes closed, making these alternatives especially useful. Nowadays, many clinicians use light bars with LED lights that move or jump back and forth to give the client something to focus on (and save the therapist shoulder pain!). The speed can be adjusted and the angle of the bar changed to provide the client with the most comfortable and effective experience possible. Again, there’s no right way to do it and, if reprocessing is stuck, a change in the direction or speed of the eye movements (or other BLS) can break through the impasse.

After the prompting of the series of questions in the Assessment phase, the client brings the disturbing memory to mind again and begins some form of BLS. The therapist instructs the client to see what comes up, as if watching a movie or scenery out the window of an advancing train. The therapist may talk intermittently throughout the reprocessing (“Just let it come,” “You’re doing great,” “Keep breathing easily,” “It’s just old stuff”); this creates a dual consciousness for the client, being caught up in past memories while still aware of being present in the here-and-now of the therapy office. The client can stop at any time, which adds to a sense of safety and control.

As the BLS proceeds, memories may emerge of related incidents from other times in the client’s life or the target memory may change and new details become noticeable to the client as the reprocessing continues. The therapist intermittently stops the BLS, instructs the client to take a deep breath and asks, “What are you getting now?,” directing the client to go with whatever emerges.

Sometimes clients report that the image has not changed after several sets of eye movements. This is known as “looping.” The therapist may then suggest the client consider something different about the image (“What if she could talk back?” or “Could anyone else join this scene?”). This is known as the “Cognitive Interweave” and may effectively get the reprocessing moving again. As the client experiences various images and memories, repressed emotions often emerge (aka abreaction). This can be very painful, but is very much the goal of treatment. Once the repressed emotion has been released, clients usually report great relief. Some clients do not even feel upset by the process, but report a sudden shift in perspective until the memory no longer seems upsetting.

Installation Phase

The Installation phase of the treatment involves revisiting the VOC and determining that the positive cognition feels completely true to the client. If it does, we move on to the Body Scan phase, in which the client is invited to scan for tension or discomfort in their body. More sets of BLS are undertaken until the tension is neutralized. The Closure phase may involve taking time to visualize the safe space or do other things to help the client contain any remaining upsetting material or sensations until the next session.

It is not uncommon for clients to feel emotionally raw after this work, and vivid dreams are not uncommon. We suggest clients keep a journal to allow for further processing (and reprocessing) of thoughts, feelings, and new memories released by the EMDR. If there is lingering disturbance associated with the original memory in subsequent sessions (the Reevaluation phase), further reprocessing may be undertaken.

After EMDR, clients often report that they no longer find the target memories disturbing. The client understands that the trauma is in the past, and they are no longer vulnerable to the same victimization or terror, either because their environment has changed or they now have resources with which to respond to dangers effectively. The memory has not disappeared, but the negative emotional effect it has on the client has been neutralized.

How Does EMDR Work?

EMDR is based on the idea that repressed emotions can be stored in the body, causing physical as well as mental illness – a tenet more readily accepted by native and Eastern medical traditions than our Western medical models. That being said, advances in neuroscience are opening up our understanding to the importance of the mind-body connection in treating mental illness, even as a great deal remains mysterious and probably always will.

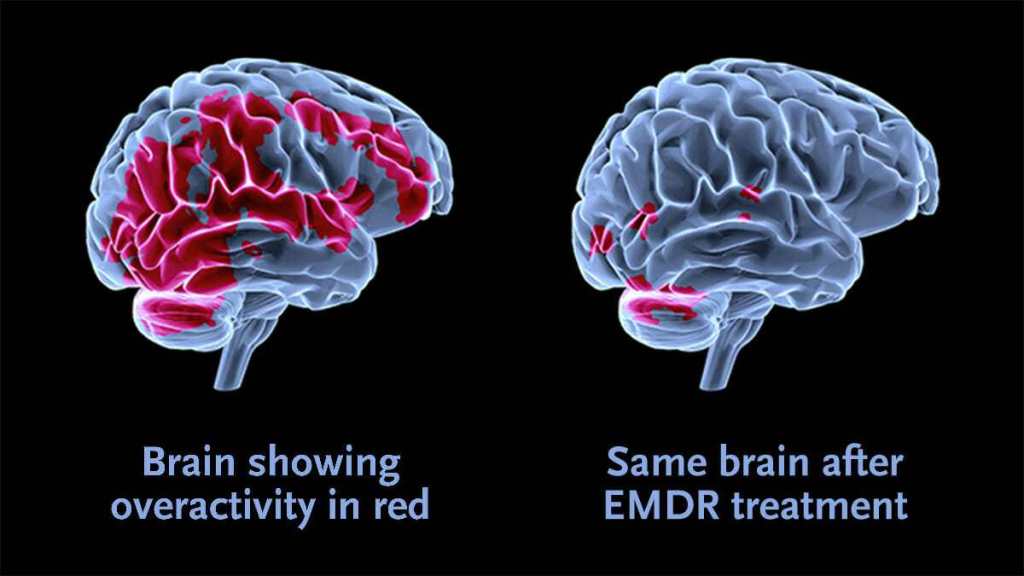

Nobody can say for sure how EMDR works, but one theory is that different parts of the brain are utilized for different functions and the interplay between the right and left hemispheres of the brain (as stimulated by the BLS) may have something to do with how reprocessing works. BLS can also be used for what is called “Resource Installation,” a variation on positive cognition reinforcement, which helps people gain access to positive states of mind. This is helpful when clients have trouble managing their emotions, establishing feelings of safety, or need ego empowerment, either in conjunction with the EMDR process or in the pursuit of other therapeutic goals.

Another theory posits that, as in REM sleep, the movement of the eyes back and forth is related to our ability to sift through the events of the day, storing some experience in memory and letting others go entirely. Unlike most memories that can be recalled with some distance from the original experience, traumatic memories have the power to reignite the fight/flight/freeze reaction that accompanied the traumatic event, making it seem like it is happening all over again in the present.

Some clinicians describe EMDR as a process that allows us to get “unstuck” from this pattern of repetition. It’s as if the traumatic memory is a log that has become wedged in a stream, causing the flow of experience to become backed up; once that “log” is dislodged, our natural ability to process our feelings and experiences without terror is restored.

In my own psychotherapy practice, I’ve used EMDR to treat clients with all sorts of issues, from accidents to incest. Although remarkably effective in the majority of cases, EMDR may not be as immediately curative for those who have experienced prolonged childhood neglect or abuse. Such traumas often cause developmental complications and reliance on emotional defense mechanisms (like dissociation, for example) that allowed clients to survive the challenging conditions of the past. The adaptations the client made in childhood may have become habitual defenses and in adulthood actually be preventing, rather than enabling, coping in healthy ways. In these cases, along with , in desensitizing particular memories, clients must unlearn or replace dysfunctional defenses with better strategies and behaviors. (Incidentally, I am currently accepting applications for two bimonthly therapy groups in NYC that should help people in their process of overcoming traumatic experiences. “Dealing with the Past, Staying in the Present” addresses childhood trauma and “In the Aftermath of the #MeToo Movement” will focus on issues of sexual harassment, abuse and assault. Both groups will start meeting in September of 2018. Go to www.therighthelp.com for more information.)

EMDR has taken its place alongside other holistic approaches to healing in the eclectic tool kit of the modern therapist. It has helped thousands of people rid themselves of devastating and previously unresolvable suffering and its use is growing with each passing year. To learn more about trauma, EMDR, and other innovative healing approaches, I recommend you read Bessel van der Kolk’s excellent book The Body Keeps the Score, or seek out an EMDR therapist of your own. You might find the experience life changing.